Rev. Dr. Sandra Fees

Sermon Reading: from the International Forgiveness Institute

Our sermon reading is a real-life story. The author is anonymous.

Growing up in one of the most violent regions in the world has taught me that anything I care about can be taken from me at any second. As a child, I recall witnessing horrifically violent images constantly appearing on the television screen, and I still have memories of being confined in a bomb shelter during the 1991 Gulf War.

Somehow because we were children, my peers and I accepted this routine –the common ritual of periodically fitting gas masks on our heads in case a chemical attack should occur— as “normal.” We internalized the fact that any time we rode the bus there might be a terrorist attack against it (and many times there was), and we would be left to deal with the turmoil which was the reality into which we were born. We grew up with friends whose family members were brutally murdered in the middle of the street and who lost body parts or suffered horrific burns in terrorist attacks. Under these conditions, it was, and is, easy to hate and stereotype these “terrorists,” to wish them harm and never to consider what their lives are really like and what kinds of trauma they too have suffered.

But who are these “terrorists”? Do they have a name? A family? A dream for a safe home to return to? Is our pain from their attacks any greater or lesser than their pain? Although comparing pain is a slippery slope, one cannot help but wonder if we would all become “terrorists” if we were living under the same circumstances. As it is simply expressed in the Native American proverb: “Great Spirit, help me never to judge another until I have walked in his moccasins.”

We can easily dwell on our personal traumas and forget that violence and loss are universal conditions that people experience every minute all over the world. . . .

What I have learned from my personal experience and relationships with those families who have lost loved ones is that forgiveness is a practice. In order to move through the trauma of my early years as an Israeli, I chose to adopt forgiveness and peace-work as a way of life. I understand how extremely short and fragile our lives are, and how crucial it is to place harmony with our environment as a priority. I have determined that spending our time in bitter punishment instead of restoring balance doesn’t help anyone. (“Grateful for Forgiveness,” September 23, 2018, https://internationalforgiveness.wordpress.com/2018/09/23/grateful-for-forgiveness/)

Sermon

Forgiveness is a spiritual practice that is taught by the world’s religions. In Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, Unitarian Universalism, and other faith traditions, forgiveness is a central tenet of living one’s faith. In some religions, the practice of forgiveness is rooted in God’s mandate to forgive. In others it is a practice rooted in compassion and well-being. But in each religion and in secular life, forgiveness is understood as an act of love and virtue that benefits everyone.

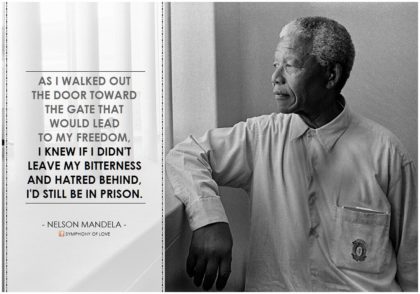

Because forgiveness heals. It improves relationships and lessens disappointment, anger, and resentment. It liberates people and groups from the pain and trauma of the past so they can live more fully in the present and into the future. According to Nelson Mandela, “As I walked out the door toward the gate that would lead to my freedom, I knew that if I didn’t leave my bitterness and hatred behind, I’d still be in prison.”

Ultimately, “forgiveness has no downside.” According to Dr. Peter Breggin, “a renewal of our capacity to forgive can only improve our inner life and empower us in every activity we undertake.” Breggin is a Harvard-trained psychiatrist and author of books and peer-reviewed scientific articles. (International Forgiveness Institute, https://internationalforgiveness.com)

So . . . if forgiveness has no downside, why do we so often act as if it does? Why don’t we forgive more often and more easily? Why is it so hard? And why do we sometimes even resist forgiving?

Those are huge questions. And there isn’t just one answer. Part of the difficulty has to do with the misconstrued expectations we bring to the practice of forgiveness.

For one thing, too often there’s a focus on forgiving and forgetting. That’s likely to get in the way of our being able to make progress on healing rifts. Forgiving doesn’t mean we forget what happened. If we expect that forgiving will lead to forgetting, we may be creating an unrealistic and unattainable expectation for ourselves.

Forgiving also gets confused with condoning what someone has done. That’s going to get in the way too. I find myself struggling with this one. If someone I love hurts my feelings, I want an apology. And I’m usually willing to accept the apology—given time. But I can get a little hung up on that, on needing the other person to apologize and acknowledge that their words or actions were unacceptable. In the absence of an apology, it’s even more complicated. I sometimes find it hard to let go of my anger at all.

I don’t want the person to get the idea that I’m okay with how they’ve treated me or with what happened. I don’t want them to forget the pain they caused me. The reality is that forgiveness with or without an apology doesn’t mean that the betrayal or injury was okay. Forgiveness is as much or more about releasing ourselves rather than the other person from the prison of negative feelings.

Confusing forgiveness with condoning the behavior is related to another unhealthy expectation. Sometimes we only want to forgive if another person is willing to change. That’s a tough one. Have you ever said that? “I’ll forgive you, this time. But don’t ever let it happen again.” Or, “I’ll forgive you this time but you are going to need to change.”

Forgiveness doesn’t work like that. Though I have certainly sometimes wished it did. It won’t ensure that the other person will change. And if we hold back forgiving until we feel certain the other person will change, we may find that we’re never able to forgive. Even where there is an intention for change, none of us is perfect.

So it’s important not to confuse forgiveness with change. In our relationships, we break trust and need to forgive each other many times over the course of our lives. Sometimes there are patterns of betrayal. Some of the breaches require us to consider deeply whether we can stay engaged with another person, institution or group that has harmed us.

Sometimes we may need to choose to forgive someone without putting ourselves in a position where we can be re-injured or re-traumatized. This can be another barrier to forgiveness, thinking that it means we need to have the same relationship as before or that we will remain in or establish personal relationship with the person or group that injured us.

There are times when boundaries need to be established for our protection. In cases of assault, repeated serious betrayals, and terrorist attacks, for example, even when there is forgiveness, that doesn’t necessarily mean that there’s going to be an ongoing personal relationship. If someone has lost a family member through a brutal murder, they may come to be able to forgive the murderer. That doesn’t mean they need to spend time with that person or put themselves in harm’s way.

There are other expectations that can get in the way of forgiveness. Have you ever put expectations on yourself around how soon you should forgive? Have you ever felt that you were supposed to forgive immediately and fully, right now, on a schedule? That can create tremendous pressure and obligation. The truth is, forgiving can take weeks or months—even years. Often forgiveness evolves slowly over time and has to be revisited.

Each of us moves at a different pace and different situations may be more difficult to forgive than others. Trying to force ourselves into quick forgiveness can backfire. If a person already feels anger and resentment, and then has the added pressure of having to forgive and finding themselves unable to forgive, that’s going to create more pain and more resentment.

And last, but certainly not least, expecting forgiveness to erase all the pain associated with a betrayal or injury can also get in the way. According to clinical psychologist Janis Abrahms Spring,

When somebody has deliberately betrayed you, and something reminds you about what that person has done, it’s natural to still feel hurt or resentment or even spasms of hate. Forgiveness doesn’t mean you lose all negative feelings forever. But it does mean that the hurt is no longer center stage. (“The Art of Forgiveness,” Linda Wasmer Andrews, September 7, 2017, https://experiencelife.com/article/the-art-of-forgiveness/)

What we can expect of forgiveness is that the hurt will no longer be center stage. The hurt will no longer be the focal point of our lives.

In our sermon reading this morning we heard the story of an Israeli woman who focused her attention on forgiving so that hurt would no longer be center stage. Having experienced the fear and turmoil of terrorist attacks, she chose forgiveness. Having grown up with friends whose family members were brutally murdered, she chose forgiveness.

She chose to center peace and compassion in herself, her relationships, and the world. She recognized that there was no downside to forgiveness. And in fact, she saw that there was an amazing upside.

One of the ways that we can embrace forgiveness is by setting positive intentions and expectations for it. We can do this by taking “The Forgiveness Pledge.” This pledge is on the website of the International Forgiveness Institute. I’m going to give you a copy in just a minute.

The International Forgiveness Institute is a world-wide nonprofit. They describe their mission as “helping people gain knowledge about forgiveness and [using] that knowledge for personal, group, and societal renewal.”

The Institute sees forgiveness as a choice. It’s a choice that releases anger and resentment to make way for hope. It may benefit the person who is forgiven. But it primarily liberates the one who is forgiving. It allows the person who forgives to reclaim their life, “restore healthy emotions, rebuild relationships and establish more peaceful communities around the world.”

Each of us can become what the Institute calls a “Peace Builder” by signing the Forgiveness Pledge.

hand out the pledge

Let’s read the pledge together.

Forgiveness Pledge

By signing this Forgiveness Pledge, I affirm that:

Forgiveness is an important part of my life.

I will do my best to forgive people from my family of origin.

I will be a conduit of forgiveness in my family.

I will forgive in the workplace and do my best to create a forgiving atmosphere.

I will encourage forgiveness in my place of worship so that it is a forgiving community.

I will do my best to plant and promote forgiveness in my wider community.

I commit to living the forgiving life.

(“The Forgiveness Pledge,” https://internationalforgiveness.com/forgiveness-pledge.htm)

I hope today or sometime this week, you will consider signing the pledge. You can make that pledge for yourself by signing that sheet of paper you have in your hand. You can also make it a more public statement by going to their website and signing up. You can post this on a mirror, place it by your bedside, on your desk at home or work, or in the car to be reminded to begin again in love.

This is a way to practice building bridges instead of fences. This is a way to practice building those bridges in our families, workplaces, church, other institutions, and worldwide.

Forgiveness is not only about healing the interpersonal relationships of many individuals. It is also restoring and has restored nations and communities around the world, in places like Northern Ireland and South Africa.

The Israeli woman who shared her experience of forgiveness in our sermon reading went on to describe the impact of forgiveness. She says:

How can we balance our needs to survive in our competitive modern world with the need to be compassionate and forgiving? For me, this juggling act of balancing the fragile scales of justice and mercy became easier once I uncomfortably realized that the capacity to inflict harm dwells in all human beings and that I myself cause harm unintentionally pretty much every single day. This understanding created an overwhelming emotion . . . . But I do believe we have a choice in transcending these animalistic tendencies by daring to embrace forgiveness and compassion, for the lives of all those involved in the conflicts. This path of action is not a quick fix, but nevertheless, it is possible.

I believe that when we compassionately and respectfully consider the needs of others, we open a new gate of communication which re-humanizes our enemies and inches us towards a solution where it is possible that everyone’s needs are met. (https://internationalforgiveness.wordpress.com/2018/09/23/grateful-for-forgiveness/)

Forgiveness has no downside. We can each inch toward forgiveness and solutions that help to ease the anger, violence, and trauma in ourselves and in our world. We can pledge ourselves anew to the high cause of greater understanding. (reference to hymn #318 “We Could Be One,” in Singing the Living Tradition hymnal)

We can forgive ourselves and each other. We can begin again in love.

Let us pledge ourselves anew to forgiveness.

May it be so. Amen. Blessed be.